From Escape Rooms to Mixed-Reality Learning Experiences: A Q&A With Stephanie Knight

Stephanie Knight is not only a personal friend but also a wealth of knowledge in the field of language learning. So, what do you do when a good friend works in the field of world languages? Interview them, of course!

![]() Meg: Tell us about your current role at the University of Oregon’s Center for Applied Second Language Studies and how your own educational experiences led you to what you do now.

Meg: Tell us about your current role at the University of Oregon’s Center for Applied Second Language Studies and how your own educational experiences led you to what you do now.

Stephanie Knight: I am the Assistant Director of CASLS, a Title VI National Foreign Language Resource Center. In that role, I have the honor of working with educators around the country at the classroom, district, and state levels. I also create curricula, develop various pedagogical tools, and engage in research related to improving language learning outcomes for all.

Meg: A big part of what you do now is design and implement mixed-reality communication and language learning experiences for educational and professional purposes. Tell us about some of your favorite projects and the journey from idea to reality.

SK: I sometimes joke that my love language is escape rooms. I went to my first one five or six years ago, and I was inspired by the way the medium catalyzed collaboration among strangers and motivated players to devote very focused attention to materials. It seemed like a medium we could reimagine in language learning contexts to promote high-level social and cognitive engagement.

Our team, under the direction of Dr. Julie M. Sykes, began to explore the ways we could operationalize some of the mechanics from escape games in mobile locative experiences that utilized mixed-reality technologies. Our first creation for the project, which is now called Virtual and Augmented Reality for Language Training (VAuLT), was a ghost hunt through part of Montreal in which players learned about the folklore surrounding Simon McTavish and how to best communicate in French with McTavish according to his communicative preferences. Since then, we have built two other mobile locative mixed-reality experiences, a full classroom experience in Spanish, a day-long professional collaboration event, a mixed-reality training in intercultural communication, and are in the process of developing a 21st Century Global Competence curriculum for elementary learners that includes training in 18 different languages.

For me, the most compelling lesson is that educators must celebrate productive frustration and, relatedly, relish and protect underspecification within learning experiences.

We are still learning lessons as we iterate. For me, the most compelling lesson is that educators must celebrate productive frustration and, relatedly, relish and protect underspecification within learning experiences. Doing so invites learner-led inquiry and exploration of key concepts.

Take a listening activity for example. In a traditional approach to practicing and evaluating listening, learners receive a series of comprehension questions, listen to the associated media (usually twice), and check their answers with the teacher. Sometimes, instruction related to listening strategies is included while learners check their answers, and sometimes, learners are allowed to listen again to see if they can identify the correct answers in the media.

This approach is typical and has served many learners, including me, for years. It is largely valid and reliable as an assessment instrument, and it meets the expectations of learners.

However, what if we did something that encouraged more learner voice?

In our Spanish-language mixed-reality experience, learners are tasked with finding a colleague who has disappeared somewhere in Latin America. The only clues they have to go off of are a weather report, a map of the Western Hemisphere, and a series of unmarked postcards from different cities in Latin America. They know they have to listen to the weather report, but what for? What are they paying attention to?

So they listen. They note what they can understand the first time through. Group members confirm details like it’s snowing in the Andes and that it is windy in Mexico with one another. However, they still don’t know why this weather report is a clue. So, they listen again.

![]() This time, someone in the group notices something. The postcards are from cities that are in the countries mentioned in the weather report! They pause and discuss. Is one mentioned twice? Is one not mentioned? They listen again to confirm.

This time, someone in the group notices something. The postcards are from cities that are in the countries mentioned in the weather report! They pause and discuss. Is one mentioned twice? Is one not mentioned? They listen again to confirm.

The next time through, they realize that the weather report mentions only five countries and that each country corresponds to a postcard. Hmmm. The missing colleague must be in one of these places, but how will they figure out which one?

So, they listen again. Suddenly, someone realizes that the images on the postcards correspond with the descriptions of the weather in the forecast! Well, that is, for all of the countries except for one. That location must be where the missing colleague is located! Using AR technologies, they scan the postcard to confirm.

Undoubtedly, the second experience invites and celebrates the learner differently than the first. In both cases, learners are listening and coming up with answers that are either correct or incorrect. However, in the second one, they are active agents in the creation of meaning. They are not simply asked to interpret meaning, but rather to uncover it. In other words, the ambiguous nature of the task invites them to pay attention differently. Further, they choose the hard work of listening to the weather report multiple times so that they can find the answer. Likely, their focus and their time on task are increased when compared to the first activity.

Also, importantly, teachers are still very active participants. However, their job is related in a very real way to the frustration I mentioned before. Teachers must celebrate the frustration that oftentimes accompanies ambiguity because it fuels the learning. However, teachers must provide a clue or suggestion of strategy before the frustration makes learners wish to quit. In this sense, the job of the teacher is that of a guide.

Meg: How big of an impact do you think the incorporation of digital and mixed-reality tools has (and will have!) on language learning experiences?

SK: At this point, the biggest impact of digital media in language learning contexts is likely the improved accessibility of content. Mostly gone are the days of teachers using their family vacations to record people abroad; a quick search on YouTube will yield lots of potential sources in most (but not all) languages. Further, low-cost or free mobile apps and digital games afford learners the opportunity to learn content without a teacher by their sides.

However, this focus on digital tools as vehicles for content delivery yields a situation in which the positive affordances of the tools often go unrealized. For example, many researchers have noted that mobile apps enable community exploration, community building, just-in-time feedback, and real-time communication. However, most mobile apps provide simple activities that are focused on grammar and vocabulary and privilege standard language. As such, learners may have some grammatical competence, but they are oftentimes undeveloped in terms of their pragmatic and intercultural competence. Unsurprisingly, they try to have a few conversations with target language speakers, fail, and inaccurately attribute that failure to a lacking capacity to learn. I believe that the focus on grammatical competence and this struggle is largely to blame for the attrition rate we see in formal language learning contexts like classrooms, and even in the informal language learning contexts like mobile apps themselves. By focusing solely on grammatical competence in easy-to-evaluate ways like fill-in-the-blank activities, we are not centering learners as active agents in the creation and understanding of meaning.

Meg: Thinking about incorporating these technologies in the classroom, what are the biggest challenges you see for teachers and students?

SK: The biggest challenges I see relate back to my previous answer; we utilize tools that are temporarily engaging, but ultimately fall short of enabling the communicative, intercultural, and pragmatic competencies of our learners. These tools are accessible, but ultimately destructive when learners do not understand the strengths and limitations of the tools.

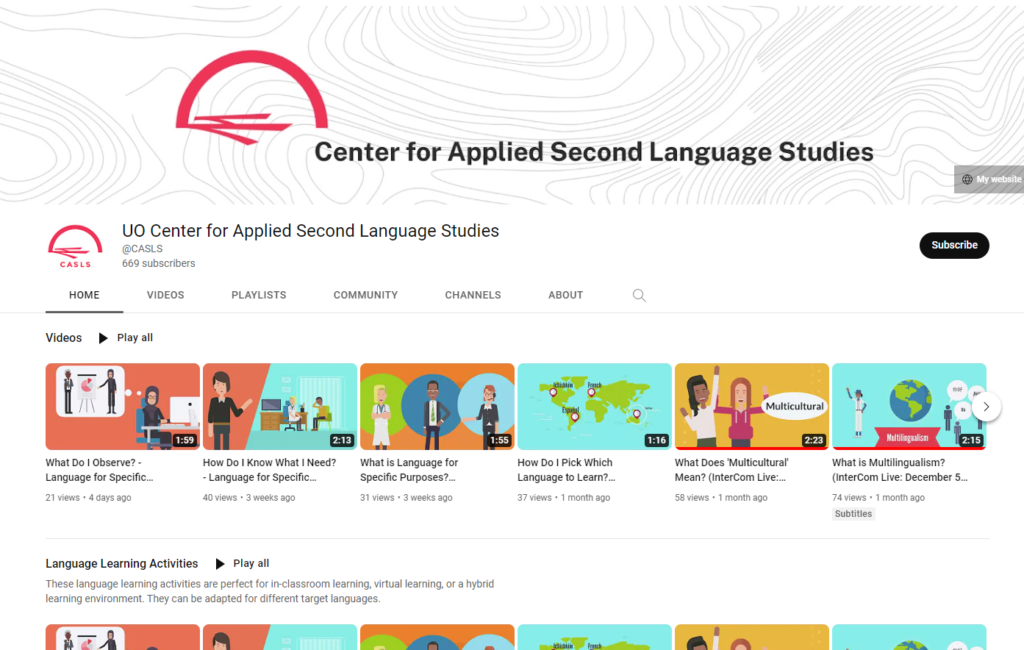

One way that we are responding to this issue is through the creation of our YouTube channel. This channel, typically updated weekly, provides language learners with bitesize example language learning activities, strategies for language learning, and reflection activities. Each video guides learners by modeling what to think about and pay attention to as they engage with language, no matter how they access the content. In our few focus groups with learners, we have found that learners respond really well to these videos. They demystify the process of learning to communicate in another language. As a bit of a plug, check it out and subscribe! We’d love to create even more content, and subscriptions really help us do that.

Meg: What are some other ways we can create more learner-focused pedagogies in the language learning classroom?

SK: Reflective practices are another way that we support the development of learner-centered pedagogies on our YouTube channel and, more broadly, with LinguaFolio Online and our work with the National Council of State Supervisors for Languages (NCSSFL) LinguaGrow Committee. This committee has been working for the past few years to iterate an updated version of LinguaFolio that really helps learners to engage with and understand the process of language learning. Specifically, learners are trained in the SPAR (Set Goals, Plan, Act, and Reflect) model and what to think about in each phase. While the LinguaGrow committee is still seeking funding to build a whole platform and mobile app to grow these resources and use of LinguaFolio Online, it is releasing some micro lessons that heavily feature CASLS resources, including the YouTube channel. These micro lessons are available for free at https://lfonetwork.uoregon.edu/micro-lessons/.

Meg: How can our audience engage with you and CASLS in the future?

SK: To find out more about the work we are doing at CASLS, subscribe to our YouTube channel and follow us on social media: Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Also, you can subscribe to our free weekly e-digest, InterCom. We send out ready-made teacher resources and curated content from third parties.

Also, if you are interested in participating in a year-long professional development group, fill out this form. We also offer additional training services according to stakeholder needs. Email [email protected] for more information.

Finally, check out some of our most recent publications!

30 January 2023 | Written by Emily Apuzzo Hopkins

Emily is the Client Solutions Manager for Meg’s US and UK markets and is based in Nashville, TN. Prior to moving into the world of EdTech, Emily spent 11 years in the classroom, teaching both music and Social Studies. Her experience ranges from early childhood education to adult professional learning. An eternal learner herself, Emily enjoys making connections through education in an effort to better understand others and the world we live in. Connect with her on LinkedIn or Twitter: @fromstagetosage.

Emily is the Client Solutions Manager for Meg’s US and UK markets and is based in Nashville, TN. Prior to moving into the world of EdTech, Emily spent 11 years in the classroom, teaching both music and Social Studies. Her experience ranges from early childhood education to adult professional learning. An eternal learner herself, Emily enjoys making connections through education in an effort to better understand others and the world we live in. Connect with her on LinkedIn or Twitter: @fromstagetosage.

Stephanie Knight holds an M.A. in Latin American Studies from the University of New Mexico and is currently seeking her Ed.D. from the University of Tennessee. Her research and development of pedagogical interventions focuses on pragmatic approaches to language acquisition and the intentional incorporation of digital and mixed-reality tools in learning experiences. She has taught all levels of Spanish to grades 5-16 and language methodology courses. Before working at CASLS, Stephanie served as the International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme Coordinator at a public high school in Tennessee.

Stephanie Knight holds an M.A. in Latin American Studies from the University of New Mexico and is currently seeking her Ed.D. from the University of Tennessee. Her research and development of pedagogical interventions focuses on pragmatic approaches to language acquisition and the intentional incorporation of digital and mixed-reality tools in learning experiences. She has taught all levels of Spanish to grades 5-16 and language methodology courses. Before working at CASLS, Stephanie served as the International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme Coordinator at a public high school in Tennessee.